One of the primary costs of deriving fuel from algae is the space required to grow the algae. Productivity of algae is calculated per acre. Algae requires sunlight and the amount of algae that can be grown on an acre is limited. Synthetic Bacteria on the other hand can produce oil without sunlight, so in comparison to algae the productivity per acre can be very high. One could theoretically grow bacteria in giant silos many stories tall. However, in order for synthetic bacteria to produce oil without sunlight they must consume sugar for energy. According to a recent article in Popular Mechanics, current technology still requires sugars to come from an easy to use source of sucrose such as sugar cane or corn. This means that synthetic bacteria fuel will compete for food stocks much the same way ethanol does, driving up the price of both. Technologies to easily derive sugars from nonfood stock cellulosic material, such as corn's remaining stalks, leaves and cobs, do not yet exist. Furthermore, even when they are developed, it estimated that it would take one acre to produce 2,000 gallons of fuel. Algae by comparison is expected to yield over 30,000 gallons per acre. On the other hand, cellulosic materials may be cheaper and easier to grow and harvest than algae.

One of the primary costs of deriving fuel from algae is the space required to grow the algae. Productivity of algae is calculated per acre. Algae requires sunlight and the amount of algae that can be grown on an acre is limited. Synthetic Bacteria on the other hand can produce oil without sunlight, so in comparison to algae the productivity per acre can be very high. One could theoretically grow bacteria in giant silos many stories tall. However, in order for synthetic bacteria to produce oil without sunlight they must consume sugar for energy. According to a recent article in Popular Mechanics, current technology still requires sugars to come from an easy to use source of sucrose such as sugar cane or corn. This means that synthetic bacteria fuel will compete for food stocks much the same way ethanol does, driving up the price of both. Technologies to easily derive sugars from nonfood stock cellulosic material, such as corn's remaining stalks, leaves and cobs, do not yet exist. Furthermore, even when they are developed, it estimated that it would take one acre to produce 2,000 gallons of fuel. Algae by comparison is expected to yield over 30,000 gallons per acre. On the other hand, cellulosic materials may be cheaper and easier to grow and harvest than algae.

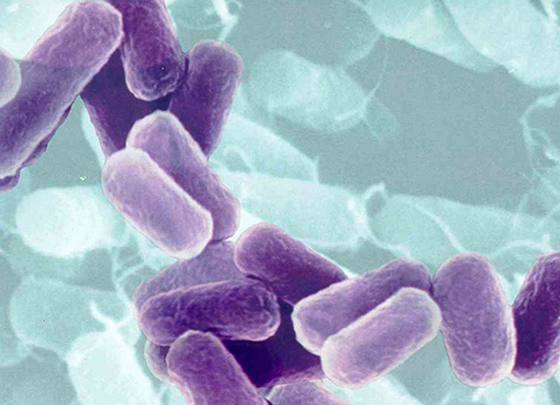

Algae and bacteria both accumulate a lot of lipids, but they do so for different reasons. When bacteria accumulate a lot of lipids, they do it when they are growing fast. That is ideal. Algae do the opposite, and produce high lipids when under stress, and are not growing very well.